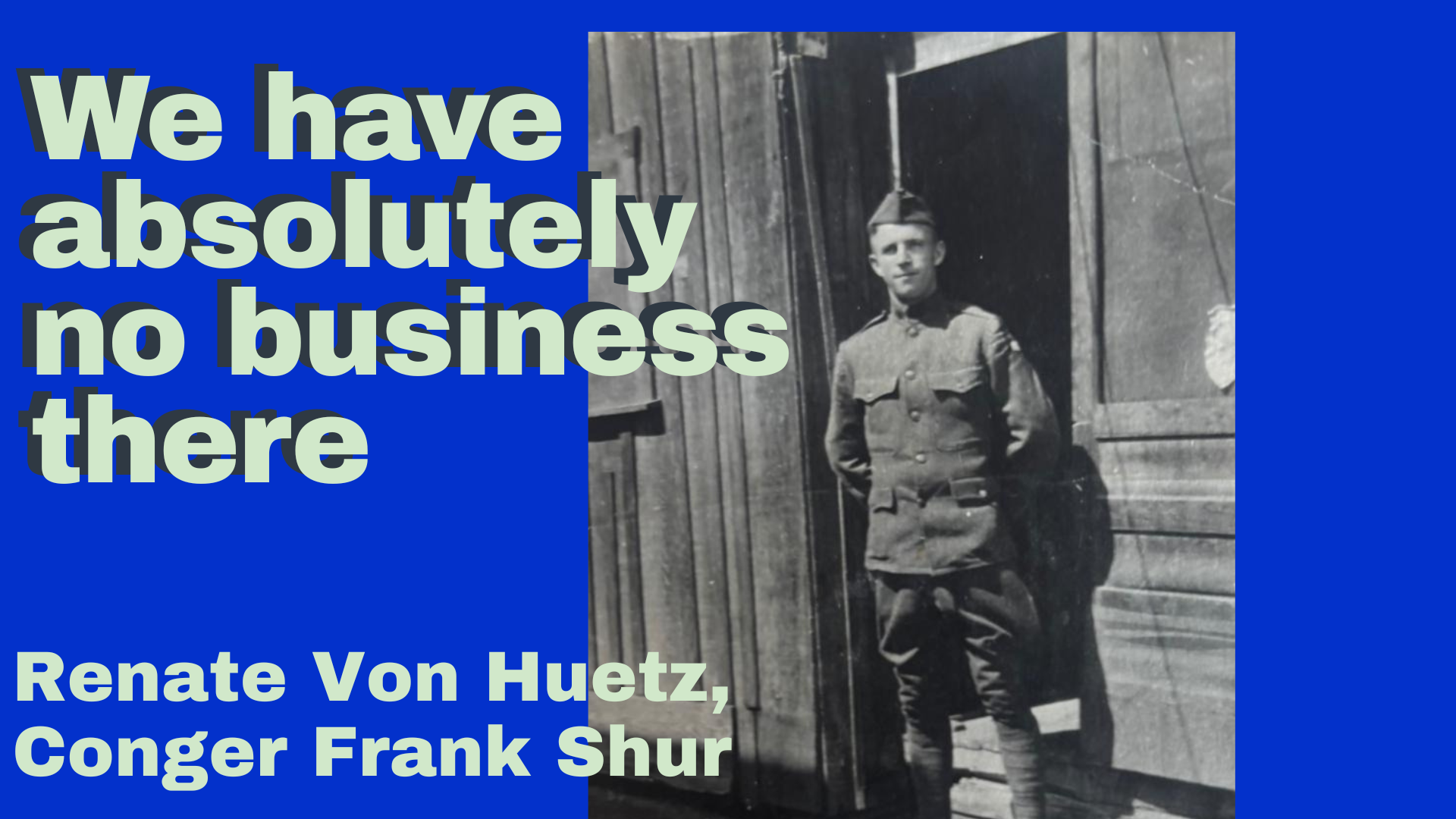

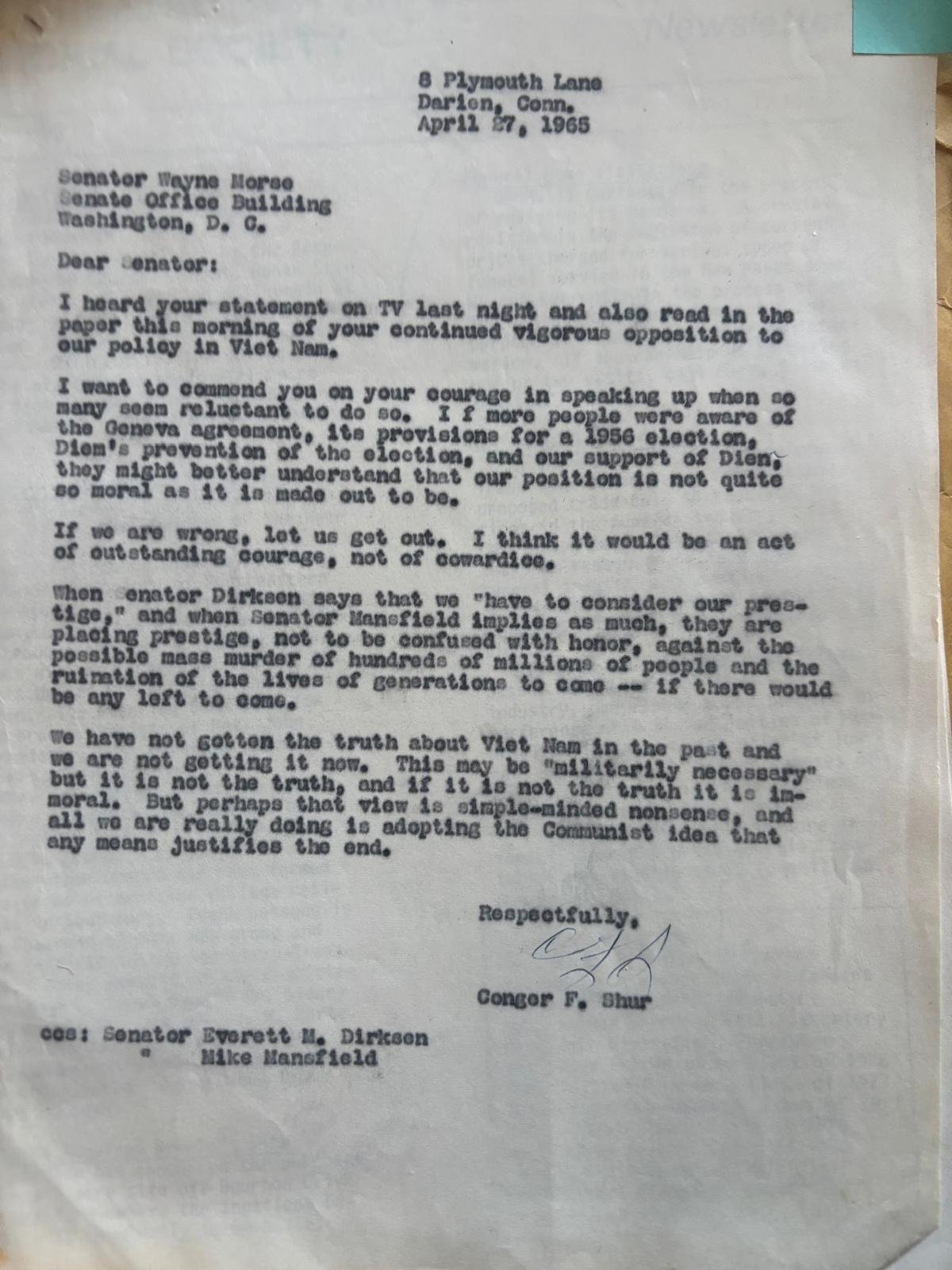

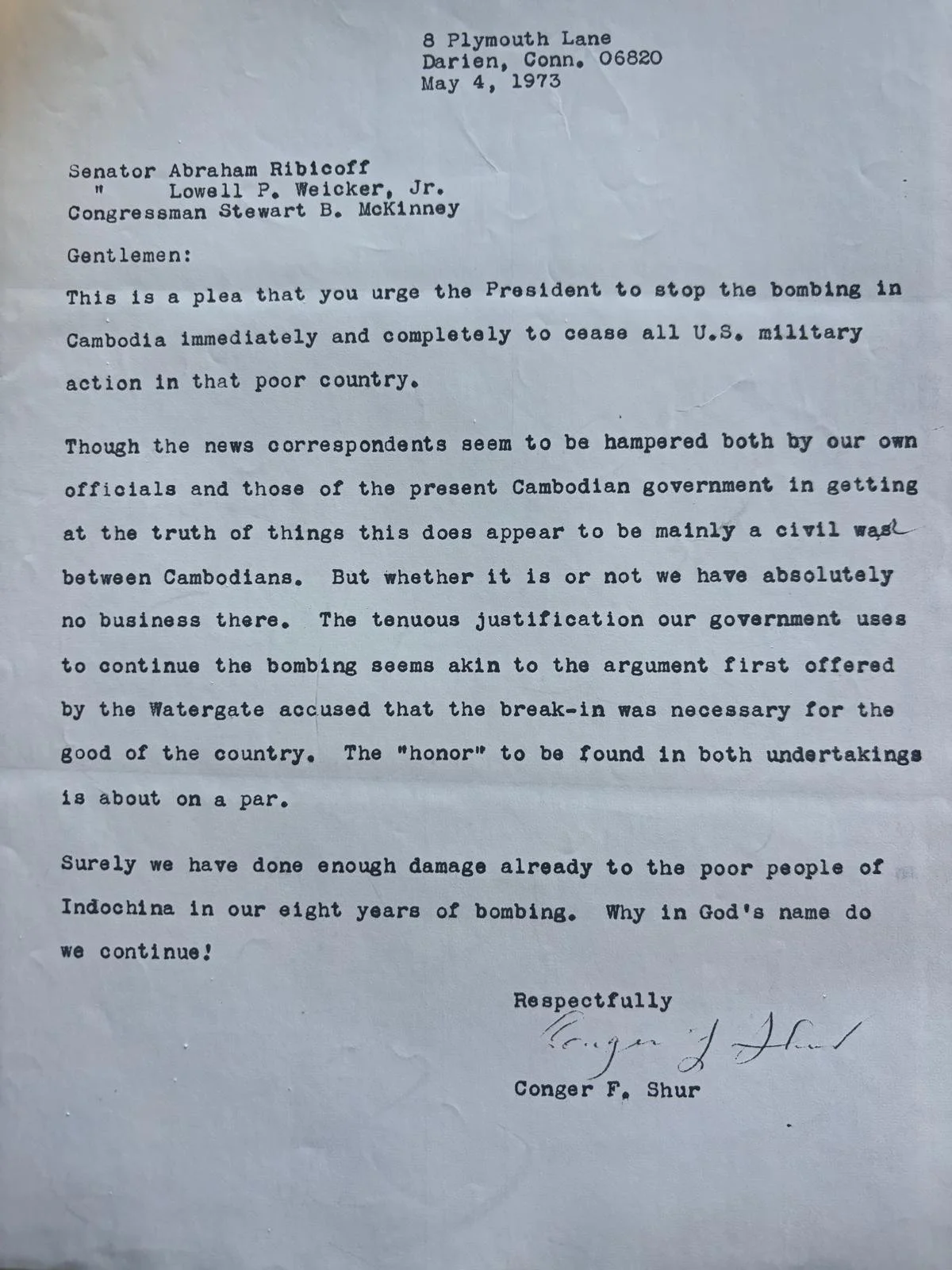

Born in 1896, my grandfather, Conger Frank Shur, was orphaned early. His formal education ended in the eighth grade, and he began his working life at thirteen as a farmhand. Although it hardened him in some ways, his Dickensian childhood gave him a rare moral clarity in certain matters. I remember hearing—long before anyone in my world or his gave any thought to animal suffering—his pained description of the way calves on the farm were taken from their mothers and kept in solitary dark enclosures until slaughter. He could never eat veal, and though this abstention was a small thing, I see it as one of many signs of how afflicted he was by empathy for others. That same empathy seems to me at work in the vast number of letters protesting the war in Vietnam that he wrote to presidents, senators, and members of congress. In the letters, which began in 1965 and continued though the American withdrawal, he is a Cassandra, warning against the evils that would come of the United States’ involvement, never being heeded, and, tragically, time after time, being proven right. I remember too, well before President Johnson sent U.S. troops, that Conger’s opposition to such a measure was regarded by the adults in the family as perverse. Although he was never, temperamentally or philosophically, anybody’s idea of a radical, it was his conscience, and not party orthodoxy, that guided him. The reader can be forgiven for thinking that his tireless letter writing campaign was no more helpful to the Vietnamese and Americans whose lives were ended or blighted by the war than his abstention from veal was to calves. I can only say that there was for me, in a world in which complacent party loyalty determined one’s position on matters domestic and foreign, a kind of quiet heroism in his independence and insistence on challenging that complacency.